February 4th, 2018

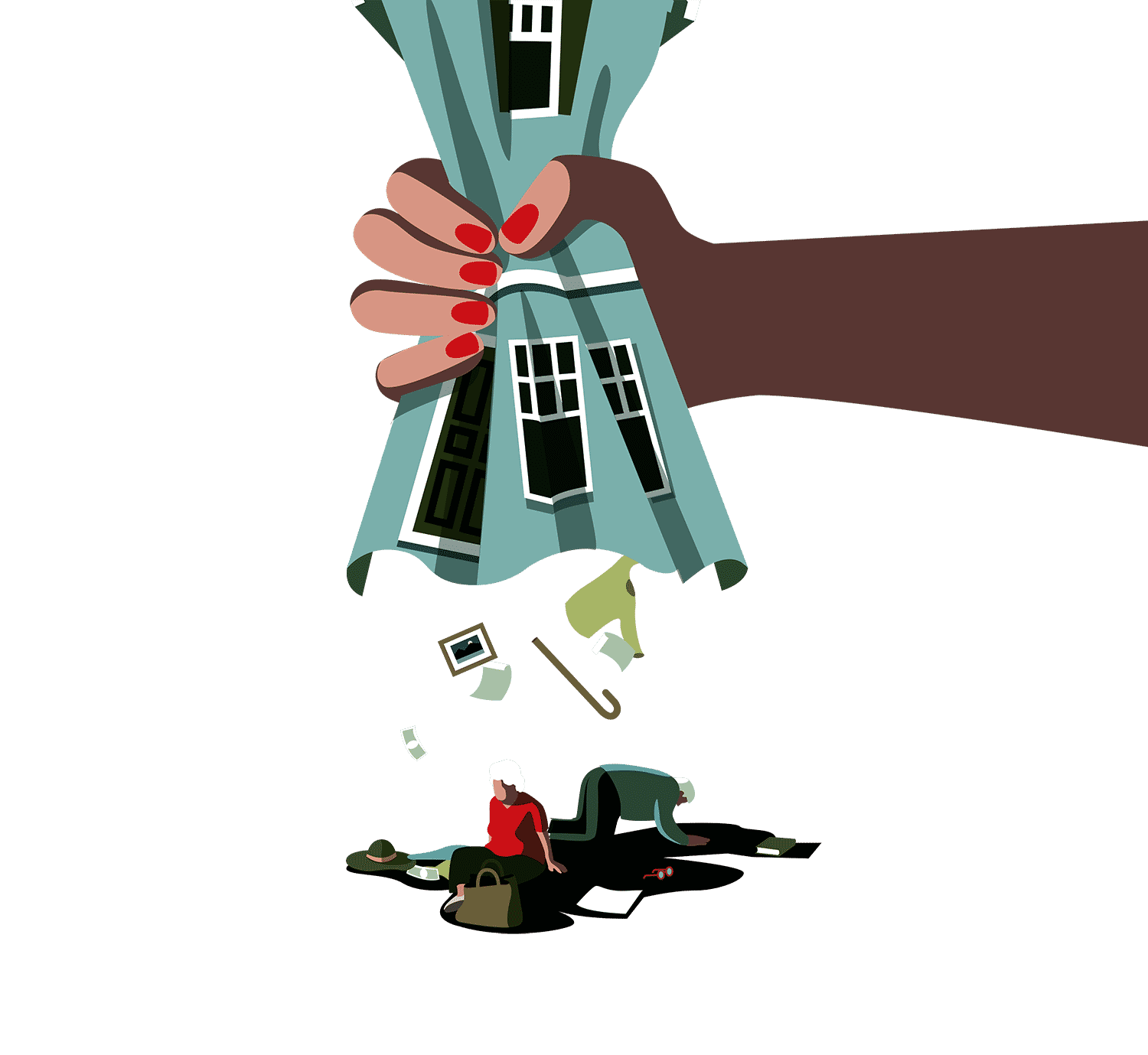

For your Bits this weekend we get started by looking at the system of state-sanctioned guardianship that allows a court-appointed guardian to take complete control of a person’s finances and freedom of movement without that person’s knowledge or consent. Based on an English legal statute from 1324, the concept of guardianship is based on the idea that the state has a “duty to act as a parent for those considered too vulnerable to care for themselves.” 1.5 million adults in the United States are under the care of guardians, whether they need to be or not, and have little recourse to remove themselves from the situation. In Clark County Nevada the system is particularly perverse with temporary guardianship frequently awarded on an ex-parte basis in a matter of minutes because guardians tell the court that they “had to intervene immediately because the ward faced a medical emergency that was only vaguely described: he or she was demented or disoriented, and at risk of exploitation or abuse.” These guardianships are then, usually, made permanent turning over a lifetime of assets to the guardian despite protestations from wards and their families.

How The Elderly Lose Their Rights

~ 41 Minute Read

“Acting as her own attorney, Williams filed a racketeering suit in federal court against Shafer and the lawyers who represented him. At a hearing before the United States District Court of Central California in 2009, she told the judge, “They are trumping up ways and means to deem people incompetent and take their assets.” The case was dismissed. “The scheme is ingenious,” she told me. “How do you come up with a crime that literally none of the victims can articulate without sounding like they’re nuts? The same insane allegations keep surfacing from people who don’t know each other.”

In 2002, in a petition to the Clark County District Court, a fifty-seven-year-old man complained that his mother had lost her constitutional rights because her kitchen was understocked and a few bills hadn’t been paid. The house they shared was then placed on the market. The son wrote, “If the only showing necessary to sell the home right out from under someone is that their ‘estate’ would benefit, then no house in Clark County is safe, nor any homeowner.” Under the guise of benevolent paternalism, guardians seemed to be creating a kind of capitalist dystopia: people’s quality of life was being destroyed in order to maximize their capital.

When Concetta Mormon, a wealthy woman who owned a Montessori school, became Shafer’s ward because she had aphasia, Shafer sold the school midyear, even though students were enrolled. At a hearing after the sale, Mormon’s daughter, Victoria Cloutier, constantly spoke out of turn. The judge, Robert Lueck, ordered that she be handcuffed and placed in a holding cell while the hearing continued. Two hours later, when Cloutier was allowed to return for the conclusion, the judge told her that she had thirty days in which to vacate her mother’s house. If she didn’t leave, she would be evicted and her belongings would be taken to Goodwill.

The opinions of wards were also disregarded. In 2010, Guadalupe Olvera, a ninety-year-old veteran of the Second World War, repeatedly asked that his daughter and not Shafer be appointed his guardian. “The ward is not to go to court,” Shafer instructed his assistants. When Olvera was finally permitted to attend a hearing, nearly a year after becoming a ward, he expressed his desire to live with his daughter in California, rather than under Shafer’s care. “Why is everybody against that?” he asked Norheim. “I don’t need that man.” Although Nevada’s guardianship law requires that courts favor relatives over professionals, Norheim continued the guardianship, saying, “The priority ship sailed.”

When Olvera’s daughter eventually defied the court’s orders and took her father to live at her seaside home in Northern California, Norheim’s supervisor, Judge Charles Hoskin, issued an arrest warrant for her “immediate arrest and incarceration” without bail. The warrant was for contempt of court, but Norheim said at least five times from the bench that she had “kidnapped” Olvera. At a hearing, Norheim acknowledged that he wasn’t able to send an officer across state lines to arrest the daughter. Shafer said, “Maybe I can.”

Shafer held so much sway in the courtroom that, in 2013, when an attorney complained that the bank account of a ward named Kristina Berger had “no money left and no records to explain where it went,” Shafer told Norheim, “Close the courtroom.” Norheim immediately complied. A dozen people in attendance were forced to leave.”

Click To Read The Full Article In The New Yorker

Sign Up To Receive Weekend Bits In Your Inbox Every Sunday

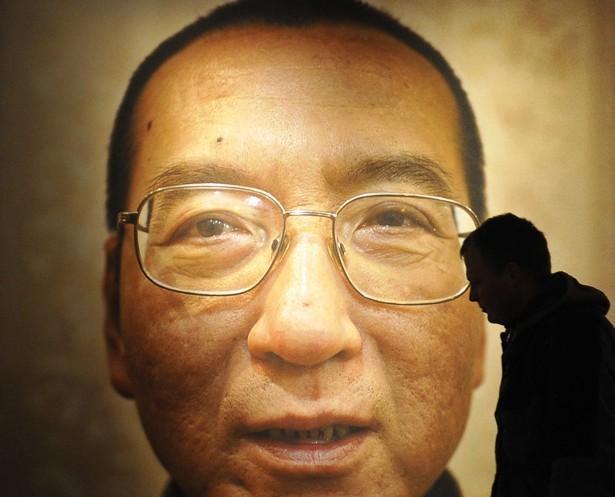

Our next article takes a look at Chinese Dissident and Nobel Peace Prize winner Liu Xiaobo. Mr. Liu is currently serving an 11 year sentence for “authoring and promoting Charter 08, a manifesto that appeals for freedom of expression, democratic elections, and human rights in China.” At his trial, Mr. Liu was given the opportunity to make a public statement, entitled “I Have No Enemies,” in which he chronicles how he became a world-renowned public intellectual during the 1980s before being arrested for “the crime of counter-revolutionary propaganda and incitement” during the June Fourth democracy protests in Tiananmen Square. Despite years of persecution by the Chinese government, Mr. Liu’s statement is focused on hope for the future of China. He highlights the progress he has seen in “the market trend in the economy, the diversification of culture, and the gradual shift in social order toward the rule of law” as well as the fair and kind way he has been treated by the people who work in the Chinese justice system. These are signs to Mr. Liu, that “there is no force that can put an end to the human quest for freedom, and China will in the end become a nation ruled by law, where human rights reign supreme.”

A Chinese Dissident’s Plea For Freedom And Love

~ 12 Minute Read

“I have also been able to feel this progress on the macro level through my own personal experience since my arrest.

Although I continue to maintain that I am innocent and that the charges against me are unconstitutional, during the one plus year since I have lost my freedom, I have been locked up at two different locations and gone through four pretrial police interrogators, three prosecutors, and two judges, but in handling my case, they have not been disrespectful, overstepped time limitations, or tried to force a confession. Their manner has been moderate and reasonable; moreover, they have often shown goodwill. On June 23, I was moved from a location where I was kept under residential surveillance to the Beijing Municipal Public Security Bureau’s No. 1 Detention Center, known as “Beikan.” During my six months at Beikan, I saw improvements in prison management.

In 1996, I spent time at the old Beikan (located at Banbuqiao). Compared to the old Beikan of more than a decade ago, the present Beikan is a huge improvement, both in terms of the “hardware”—the facilities—and the “software”—the management. In particular, the humane management pioneered by the new Beikan, based on respect for the rights and integrity of detainees, has brought flexible management to bear on every aspect of the behavior of the correctional staff, and has found expression in the “comforting broadcasts,” Repentance magazine, and music before meals, on waking and at bedtime. This style of management allows detainees to experience a sense of dignity and warmth, and stirs their consciousness in maintaining prison order and opposing the bullies among inmates. Not only has it provided a humane living environment for detainees, it has also greatly improved the environment for their litigation to take place and their state of mind. I’ve had close contact with correctional officer Liu Zheng, who has been in charge of me in my cell, and his respect and care for detainees could be seen in every detail of his work, permeating his every word and deed, and giving one a warm feeling. It was perhaps my good fortune to have gotten to know this sincere, honest, conscientious, and kind correctional officer during my time at Beikan.

It is precisely because of such convictions and personal experience that I firmly believe that China’s political progress will not stop, and I, filled with optimism, look forward to the advent of a future free China. For there is no force that can put an end to the human quest for freedom, and China will in the end become a nation ruled by law, where human rights reign supreme. I also hope that this sort of progress can be reflected in this trial as I await the impartial ruling of the collegial bench—a ruling that will withstand the test of history.”

Click To Read The Full Article In The Atlantic

Sign Up To Receive Weekend Bits In Your Inbox Every Sunday

Your last Bit of the weekend takes a look at extreme poverty in rural West Virginia, following Donna Jean Dempsey as she struggles to find ways to make money when her $735 monthly disability check is gone. Ms. Dempsey lives in a “shed the size of a one-car garage that her rental company describes as a ‘lofted playhouse’” with no running water, paying almost half her disability check for rent. By the end of the month, she is out of money and goes with her brother into the mountains to dig up roots which she can trade for a few extra dollars. Although, the law requires her to report any extra income Ms. Dempsey “believe[s] she had made it honestly — never stealing, like some, never selling drugs, like others;” she is just finding a way to get by with the options that she has.

After The Check Is Gone

~ 23 Minute Read

“And where they were going was deep into the underground American economy, where researchers know some people receiving disability benefits are forced to work illegally after the checks are spent — because they can’t hold a regular job, because no one will hire them, because disability payments on average amount to less than minimum wage, sometimes much less, and because it’s hard to live on so little.

The underground economy has long been a part of rural America, but it has become vital in counties such as this one, deprived of the once-dominant coal industry and redefined by a decades-long swell in the nation’s disability rolls that, in its aftermath, has left more than 1 in 5 working-age residents in Logan County on Social Security Disability Insurance, which serves disabled workers, or Supplemental Security Income for the disabled poor.

Some who enter this realm assume one risk — working illegally — to avoid others. Every reported dollar beyond a small amount can result in a reduced disability check or, worse, no check at all. The government awards benefits with the understanding that recipients can work only very little, or not at all, and that reporting too much in earnings can lead to being cut off.

“There is this theme of people being crooks, but it’s genuinely people trying to find a way to patch together a living when they have very little income,” said Mil Duncan, one of the nation’s leading rural sociologists. “It’s not a moral issue. It’s a getting-by issue.”

In West Virginia, getting by means digging roots in the mountains. Brent Bailey, a former assistant research professor at West Virginia University who has studied the root trade, calls it a “social safety net” that people relied on when “Plan A fell apart.” “Most of this is Plan B,” he said, “after you’ve lost your job or your disability check has dried up.”

For Donna Jean, who watched Bobby steer his truck above the forest canopy and through low-hanging mist, it was time again for Plan B.

“We’ll park right here and see what we can find,” Bobby said, pulling over beside a fallen tree and killing the engine.

Donna Jean stepped out and looked up. Dark clouds were moving in from a nearby mountain. She lit a home-rolled cigarette and, getting to work with a mattock, tried to ignore the weather. She had lately been telling herself that she had to stop taking these risks. They were more than an hour from the nearest hospital, and what if she had another heart attack? What if Bobby, allergic to bees, accidentally dug into a buried nest? And if a snake bit one of them — the month before, Bobby had killed a copperhead as it prepared to strike — could they get to help in time?

She brought down the mattock and came up with a palm-size root the dirty white of ivory.

“Find anything?” called Bobby, a tall, angular man with hardened features, some distance up the path.

“Solomon’s seal root,” she yelled, leaning into a hillside beside a scattering of surface coal. She dug out more, along with some bloodroot and “I have no idea what these are, but I’ll take them.” She took them all, hoping that a small pile of roots would turn into a big pile and that a big pile would turn into enough money to buy milk, bread and laundry detergent, only stopping when a siren sounded.

“Flash flooding,” she said.

She glanced down at the ravine, then up at the clouds. They were darker than before. She wanted off this mountain. But her next disability check was three days away, and she didn’t have enough roots, not nearly enough, so down the mattock went again.”

Click To Read The Full Article In The Washington Post

Thanks for checking out the Weekend Bits! If you enjoyed these Bits, why don’t you share it with a friend? We appreciate your support and as always, Contact Us online or send us an email at [email protected].

Have a great rest of your week!