January 28th, 2018

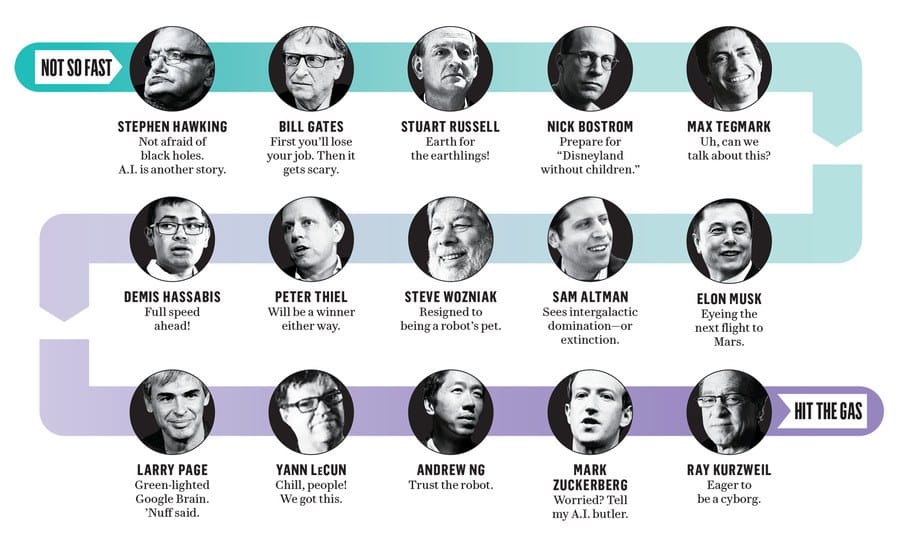

For your Bits this weekend we get started with a look at Elon Musk’s frantic effort to mitigate the potential threats posed by artificial intelligence. The world is rapidly racing to the point where artificial intelligence will be incorporated into most aspects of everyday life and, amongst experts and prominent technology leaders, opinions vary widely as to what the impact on humanity will be. Ray Kurzweil takes 90 pills a day in the hopes that he will stay alive long enough to merge with the machines while Steve Wozniak expects to be a pet for the A.I. and Stephen Hawking thinks A.I. could spell the end of the human race. Elon Musk comes down closer to the Hawking end of the spectrum and is particularly worried about A.I. created by technology companies, like Google, which might “produce something evil by accident” in their efforts towards profit maximization. Once there is a superintelligence that is smarter than humanity, we will lose the ability to take control of it or turn it off. In an effort to keep the most advanced artificial intelligence capabilities in the public domain, Musk founded the billion-dollar nonprofit company, OpenAI “to work for safer artificial intelligence.”

Elon Musk’s Billion-Dollar Crusade To Stop The A.I. Apocalypse

~ 39 Minute Read

“Eliezer Yudkowsky is a highly regarded 37-year-old researcher who is trying to figure out whether it’s possible, in practice and not just in theory, to point A.I. in any direction, let alone a good one. I met him at a Japanese restaurant in Berkeley.

“How do you encode the goal functions of an A.I. such that it has an Off switch and it wants there to be an Off switch and it won’t try to eliminate the Off switch and it will let you press the Off switch, but it won’t jump ahead and press the Off switch itself?” he asked over an order of surf-and-turf rolls. “And if it self-modifies, will it self-modify in such a way as to keep the Off switch? We’re trying to work on that. It’s not easy.”

I babbled about the heirs of Klaatu, HAL, and Ultron taking over the Internet and getting control of our banking, transportation, and military. What about the replicants in Blade Runner, who conspire to kill their creator? Yudkowsky held his head in his hands, then patiently explained: “The A.I. doesn’t have to take over the whole Internet. It doesn’t need drones. It’s not dangerous because it has guns. It’s dangerous because it’s smarter than us. Suppose it can solve the science technology of predicting protein structure from DNA information. Then it just needs to send out a few e-mails to the labs that synthesize customized proteins. Soon it has its own molecular machinery, building even more sophisticated molecular machines.

“If you want a picture of A.I. gone wrong, don’t imagine marching humanoid robots with glowing red eyes. Imagine tiny invisible synthetic bacteria made of diamond, with tiny onboard computers, hiding inside your bloodstream and everyone else’s. And then, simultaneously, they release one microgram of botulinum toxin. Everyone just falls over dead.

“Only it won’t actually happen like that. It’s impossible for me to predict exactly how we’d lose, because the A.I. will be smarter than I am. When you’re building something smarter than you, you have to get it right on the first try.”

I thought back to my conversation with Musk and Altman. Don’t get sidetracked by the idea of killer robots, Musk said, noting, “The thing about A.I. is that it’s not the robot; it’s the computer algorithm in the Net. So the robot would just be an end effector, just a series of sensors and actuators. A.I. is in the Net . . . . The important thing is that if we do get some sort of runaway algorithm, then the human A.I. collective can stop the runaway algorithm. But if there’s large, centralized A.I. that decides, then there’s no stopping it.”

Altman expanded upon the scenario: “An agent that had full control of the Internet could have far more effect on the world than an agent that had full control of a sophisticated robot. Our lives are already so dependent on the Internet that an agent that had no body whatsoever but could use the Internet really well would be far more powerful.”

Even robots with a seemingly benign task could indifferently harm us. “Let’s say you create a self-improving A.I. to pick strawberries,” Musk said, “and it gets better and better at picking strawberries and picks more and more and it is self-improving, so all it really wants to do is pick strawberries. So then it would have all the world be strawberry fields. Strawberry fields forever.” No room for human beings.

But can they ever really develop a kill switch? “I’m not sure I’d want to be the one holding the kill switch for some superpowered A.I., because you’d be the first thing it kills,” Musk replied.

Altman tried to capture the chilling grandeur of what’s at stake: “It’s a very exciting time to be alive, because in the next few decades we are either going to head toward self-destruction or toward human descendants eventually colonizing the universe.”

“Right,” Musk said, adding, “If you believe the end is the heat death of the universe, it really is all about the journey.”

The man who is so worried about extinction chuckled at his own extinction joke. As H. P. Lovecraft once wrote, “From even the greatest of horrors irony is seldom absent.””

Click To Read The Full Article At Vanity Fair

Sign Up To Receive Weekend Bits In Your Inbox Every Sunday

Our next article takes a look at the alleged rape of Shiori Ito by one of the most powerful journalists in Japan, Noriyuki Yamaguchi. Reports of sexual assault are far less common in a country where convicted rapists often serve light prison sentences (if any jail time at all) and police will usually only follow up on a report of rape if there are “signs of both physical force and self-defense” and neither person has been drinking. Ms. Ito was initially discouraged by police from pursuing her case because “she was not crying as she told [about] it,” but they eventually moved forward in the investigation based on the strength of security footage that showed her passed out while being carried through a hotel lobby and the testimony of a taxi driver who drove her and Mr. Yamaguchi. Despite this evidence, it seems that Mr. Yamaguchi’s political connections saved him as the Tokyo Prosecutors’ office did not press charges after being told to drop the case by an aide to the Japanese president’s chief cabinet secretary.

She Broke Japan’s Silence On Rape

~ 13 Minute Read

“As the United States reckons with an outpouring of sexual misconduct cases that have shaken Capitol Hill, Hollywood, Silicon Valley and the news media, Ms. Ito’s story is a stark example of how sexual assault remains a subject to be avoided in Japan, where few women report rape to the police and when they do, their complaints rarely result in arrests or prosecution.

On paper, Japan boasts relatively low rates of sexual assault. In a survey conducted by the Cabinet Office of the central government in 2014, one in 15 women reported experiencing rape at some time in their lives, compared with one in five women who report having been raped in the United States.

But scholars say Japanese women are far less likely to describe nonconsensual sex as rape than women in the West. Japan’s rape laws make no mention of consent, date rape is essentially a foreign concept and education about sexual violence is minimal.

Instead, rape is often depicted in manga comics and pornography as an extension of sexual gratification, in a culture in which such material is often an important channel of sex education.

The police and courts tend to define rape narrowly, generally pursuing cases only when there are signs of both physical force and self-defense and discouraging complaints when either the assailant or victim has been drinking.

Last month, prosecutors in Yokohama dropped a case against six university students accused of sexually assaulting another student after forcing her to drink alcohol.

And even when rapists are prosecuted and convicted in Japan, they sometimes serve no prison time; about one in 10 receive only suspended sentences, according to Justice Ministry statistics.

This year, for example, two students at Chiba University near Tokyo convicted in the gang rape of an intoxicated woman were released with suspended sentences, though other defendants were sentenced to prison. Last fall, a Tokyo University student convicted in another group sexual assault was also given a suspended sentence.

“It’s quite recent that activists started to raise the ‘No Means No’ campaign,” said Mari Miura, a professor of political science at Sophia University in Tokyo. “So I think Japanese men get the benefit from this lack of consciousness about the meaning of consent.”

Of the women who reported experiencing rape in the Cabinet Office survey, more than two-thirds said they had never told anyone, not even a friend or family member. And barely 4 percent said they had gone to the police. By contrast, in the United States, about a third of rapes are reported to the police, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics.

“Prejudice against women is deep-rooted and severe, and people don’t consider the damage from sexual crimes seriously at all,” said Tomoe Yatagawa, a lecturer in gender law at Waseda University.”

Click To Read The Full Article At The New York Times

Sign Up To Receive Weekend Bits In Your Inbox Every Sunday

Your last Bit of the weekend takes a look at how humans perceive inequality. A number of studies have shown that there are no psychological winners when it comes to inequality; people with less feel resentful while people with more don’t feel any better. In fact, people with more often don’t realize how much they have because they are too busy comparing themselves to those who have even more than them; even families with multi-million dollar annual incomes and multiple vacation homes feel poor compared to their wealthier friends who have the additional luxury of flying in private jets. Humans are hardwired to favor fairness from a young age and the subjective feeling of impoverishment driven by perceptions of inequality makes everyone worse off.

The Psychology of Inequality

~ 14 Minute Read

“Although in strictly economic terms nothing had happened—Payne’s family had just as much (or as little) money as it had the day before—that afternoon in the cafeteria he became aware of which rung on the ladder he occupied. He grew embarrassed about his clothes, his way of talking, even his hair, which was cut at home with a bowl. “Always a shy kid, I became almost completely silent at school,” he recalls.

Payne is now a professor at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. He has come to believe that what’s really damaging about being poor, at least in a country like the United States—where, as he notes, even most people living below the poverty line possess TVs, microwaves, and cell phones—is the subjective experience of feeling poor. This feeling is not limited to those in the bottom quintile; in a world where people measure themselves against their neighbors, it’s possible to earn good money and still feel deprived. “Unlike the rigid columns of numbers that make up a bank ledger, status is always a moving target, because it is defined by ongoing comparisons to others,” Payne writes.

Feeling poor, meanwhile, has consequences that go well beyond feeling. People who see themselves as poor make different decisions, and, generally, worse ones. Consider gambling. Spending two bucks on a Powerball ticket, which has roughly a one-in-three-hundred-million chance of paying out, is never a good bet. It’s especially ill-advised for those struggling to make ends meet. Yet low-income Americans buy a disproportionate share of lottery tickets, so much so that the whole enterprise is sometimes referred to as a “tax on the poor.”

One explanation for this is that poor people engage in riskier behavior, which is why they are poor in the first place. By Payne’s account, this way of thinking gets things backward. He cites a study on gambling performed by Canadian psychologists. After asking participants a series of probing questions about their finances, the researchers asked them to rank themselves along something called the Normative Discretionary Income Index. In fact, the scale was fictitious and the scores were manipulated. It didn’t matter what their finances actually looked like: some of the participants were led to believe that they had more discretionary income than their peers and some were led to believe the opposite. Finally, participants were given twenty dollars and the choice to either pocket it or gamble it on a computer card game. Those who believed they ranked low on the scale were much more likely to risk the money on the card game. Or, as Payne puts it, “feeling poor made people more willing to roll the dice.”

In another study, this one conducted by Payne and some colleagues, participants were divided into two groups and asked to make a series of bets. For each bet, they were offered a low-risk / low-reward option (say, a hundred-per-cent chance of winning fifteen cents) and a high-risk / high-reward option (a ten-per-cent chance of winning a dollar-fifty). Before the exercise began, the two groups were told different stories (once again, fictitious) about how previous participants had fared. The first group was informed that the spread in winnings between the most and the least successful players was only a few cents, the second that the gap was a lot wider. Those in the second group went on to place much chancier bets than those in the first. The experiment, Payne contends, “provided the first evidence that inequality itself can cause risky behavior.””

Click To Read The Full Article At The New Yorker

Thanks for checking out the Weekend Bits! If you enjoyed these Bits, why don’t you share it with a friend? We appreciate your support and as always, Contact Us online or send us an email at [email protected].

Have a great rest of your week!