November 12, 2017

For your Bits this weekend we start with an article about climate change and “it is, I promise, worse than you think.” The increase in sea level that accompanies climate change is just one aspect of the problem as the corresponding change in the chemical composition of the ocean and atmosphere will drive changes like: the climate in New York City becoming similar to that of Bahrain (and Bahrain becoming uninhabitable), the inability to grow food in places that today feed billions of people, ancient plagues being released from the ice and warmer temperatures allowing existing diseases like malaria to spread worldwide, the release of suffocating gases across the planet, along with an increase in wars and the strong potential for economic decline and collapse. While all of these possibilities are not inevitable, given that the planet’s deterioration will elicit some change in human behavior, we are past the point where reducing carbon emissions will solve the problem and we will have to rely on new and untested innovations like carbon capture and geo-engineering for our species to stand a chance of survival on earth.

The Uninhabitable Earth

~ 37 Minute Read

“But no matter how well-informed you are, you are surely not alarmed enough. Over the past decades, our culture has gone apocalyptic with zombie movies and Mad Max dystopias, perhaps the collective result of displaced climate anxiety, and yet when it comes to contemplating real-world warming dangers, we suffer from an incredible failure of imagination. The reasons for that are many: the timid language of scientific probabilities, which the climatologist James Hansen once called “scientific reticence” in a paper chastising scientists for editing their own observations so conscientiously that they failed to communicate how dire the threat really was; the fact that the country is dominated by a group of technocrats who believe any problem can be solved and an opposing culture that doesn’t even see warming as a problem worth addressing; the way that climate denialism has made scientists even more cautious in offering speculative warnings; the simple speed of change and, also, its slowness, such that we are only seeing effects now of warming from decades past; our uncertainty about uncertainty, which the climate writer Naomi Oreskes in particular has suggested stops us from preparing as though anything worse than a median outcome were even possible; the way we assume climate change will hit hardest elsewhere, not everywhere; the smallness (two degrees) and largeness (1.8 trillion tons) and abstractness (400 parts per million) of the numbers; the discomfort of considering a problem that is very difficult, if not impossible, to solve; the altogether incomprehensible scale of that problem, which amounts to the prospect of our own annihilation; simple fear. But aversion arising from fear is a form of denial, too.

In between scientific reticence and science fiction is science itself. This article is the result of dozens of interviews and exchanges with climatologists and researchers in related fields and reflects hundreds of scientific papers on the subject of climate change. What follows is not a series of predictions of what will happen — that will be determined in large part by the much-less-certain science of human response. Instead, it is a portrait of our best understanding of where the planet is heading absent aggressive action. It is unlikely that all of these warming scenarios will be fully realized, largely because the devastation along the way will shake our complacency. But those scenarios, and not the present climate, are the baseline. In fact, they are our schedule.

The present tense of climate change — the destruction we’ve already baked into our future — is horrifying enough. Most people talk as if Miami and Bangladesh still have a chance of surviving; most of the scientists I spoke with assume we’ll lose them within the century, even if we stop burning fossil fuel in the next decade. Two degrees of warming used to be considered the threshold of catastrophe: tens of millions of climate refugees unleashed upon an unprepared world. Now two degrees is our goal, per the Paris climate accords, and experts give us only slim odds of hitting it. The U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change issues serial reports, often called the “gold standard” of climate research; the most recent one projects us to hit four degrees of warming by the beginning of the next century, should we stay the present course. But that’s just a median projection. The upper end of the probability curve runs as high as eight degrees — and the authors still haven’t figured out how to deal with that permafrost melt. The IPCC reports also don’t fully account for the albedo effect (less ice means less reflected and more absorbed sunlight, hence more warming); more cloud cover (which traps heat); or the dieback of forests and other flora (which extract carbon from the atmosphere). Each of these promises to accelerate warming, and the history of the planet shows that temperature can shift as much as five degrees Celsius within thirteen years. The last time the planet was even four degrees warmer, Peter Brannen points out in The Ends of the World, his new history of the planet’s major extinction events, the oceans were hundreds of feet higher.*

The Earth has experienced five mass extinctions before the one we are living through now, each so complete a slate-wiping of the evolutionary record it functioned as a resetting of the planetary clock, and many climate scientists will tell you they are the best analog for the ecological future we are diving headlong into. Unless you are a teenager, you probably read in your high-school textbooks that these extinctions were the result of asteroids. In fact, all but the one that killed the dinosaurs were caused by climate change produced by greenhouse gas. The most notorious was 252 million years ago; it began when carbon warmed the planet by five degrees, accelerated when that warming triggered the release of methane in the Arctic, and ended with 97 percent of all life on Earth dead. We are currently adding carbon to the atmosphere at a considerably faster rate; by most estimates, at least ten times faster. The rate is accelerating. This is what Stephen Hawking had in mind when he said, this spring, that the species needs to colonize other planets in the next century to survive, and what drove Elon Musk, last month, to unveil his plans to build a Mars habitat in 40 to 100 years. These are nonspecialists, of course, and probably as inclined to irrational panic as you or I. But the many sober-minded scientists I interviewed over the past several months — the most credentialed and tenured in the field, few of them inclined to alarmism and many advisers to the IPCC who nevertheless criticize its conservatism — have quietly reached an apocalyptic conclusion, too: No plausible program of emissions reductions alone can prevent climate disaster.

Over the past few decades, the term “Anthropocene” has climbed out of academic discourse and into the popular imagination — a name given to the geologic era we live in now, and a way to signal that it is a new era, defined on the wall chart of deep history by human intervention. One problem with the term is that it implies a conquest of nature (and even echoes the biblical “dominion”). And however sanguine you might be about the proposition that we have already ravaged the natural world, which we surely have, it is another thing entirely to consider the possibility that we have only provoked it, engineering first in ignorance and then in denial a climate system that will now go to war with us for many centuries, perhaps until it destroys us. That is what Wallace Smith Broecker, the avuncular oceanographer who coined the term “global warming,” means when he calls the planet an “angry beast.” You could also go with “war machine.” Each day we arm it more.”

Click To Read The Full Article At NYMag.com

Sign Up To Receive Weekend Bits In Your Inbox Every Sunday

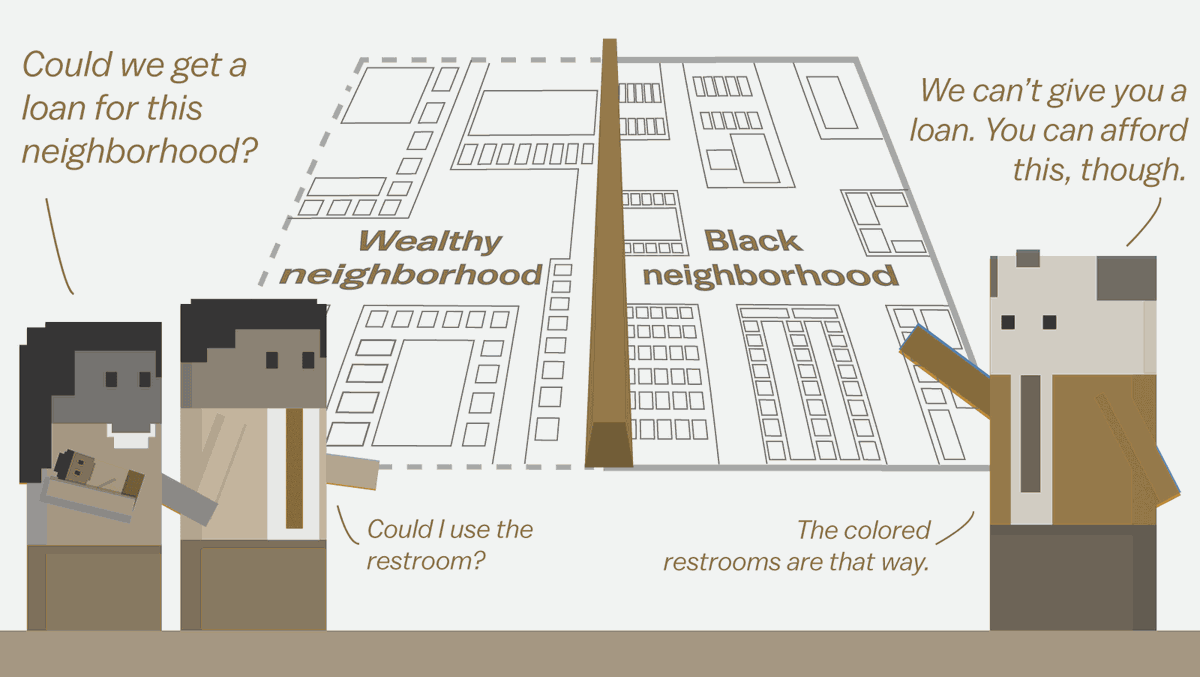

Our next article takes a look at the multitude of ways that living in a poor neighborhood makes life more difficult and the history of redlining, or the systematic exclusion of black people from obtaining housing loans in certain neighborhoods. Redlining has contributed to the lack of intergenerational mobility to the point that “if you’re black and your parents grew up in a poor neighborhood, then you probably ended up in a poor neighborhood too.” The consequences of growing up in a neighborhood of extreme poverty, where greater than 40% of residents live below the poverty line, are far reaching resulting in higher rates of depression, worse educational services, and reduced opportunities for kids to exercise that can result in lifelong health problems. Allowing high concentrations of poverty furthers generations of systematic segregation and fails to provide opportunity for the next generation.

Living In A Poor Neighborhood Changes Everything About Your Life

~ 16 Minute Read

“Oh, another thing: Living in these poor neighborhoods makes you significantly less happy, less hopeful, and less healthy

In Connecticut, Mark Abraham of DataHaven surveyed 16,000 people last year in one of the most comprehensive state surveys ever. And one of the more personal questions he asked was: How happy were you yesterday? There was an undeniable pattern. Living in a highly distressed neighborhoods — which are poor, unemployed, and undereducated — often meant you were quite unhappy[;] Quite hopeless[;] And less healthy[;] And people who lived in distressed neighborhoods didn’t think it was a good place to raise kids:

All of these things are correlated, according to Larry Finison of the Connecticut Health Foundation, who has studied neighborhoods indicators for decades. If the neighborhood has a high crime rate and it’s not safe for your kids to be outside by themselves, then you wouldn’t let your kids play outside. This means they are getting less exercise, which leads to higher obesity rates. And more health problems. And so on. In other words, living in these poor neighborhoods is really hard and unpleasant. And being poor means it’s hard to leave.”

…

“Whatever we try, we’re missing the point if we don’t talk about race

We often talk about poverty as if it’s only about the lack of money. But the most devastating part is that when a lot of people without money are pushed to live in the same neighborhood, it creates an environment that poisons a child’s ability to reach their potential.

It’s more comfortable to talk about inequality and poverty outside the context of race. More than half the country thinks past or present discrimination is not a major factor in why black Americans face problems today. But in the past, it was OK to literally build a wall between a white neighborhood and black neighborhood. That was a lot easier to point at and say: Hey, that’s racist. Now, those concrete symbols of racism are largely gone and what’s left are their systemic effects. Sometimes, that makes it hard to be as outraged.

But in this country, we forced people into toxic neighborhoods based on the color of their skin, and it still plays an overwhelming role in which people gets a real shot to be healthy, happy, and hopeful. In other words, the walls are still there.”

Click To Read The Full Article At Vox.com

Sign Up To Receive Weekend Bits In Your Inbox Every Sunday

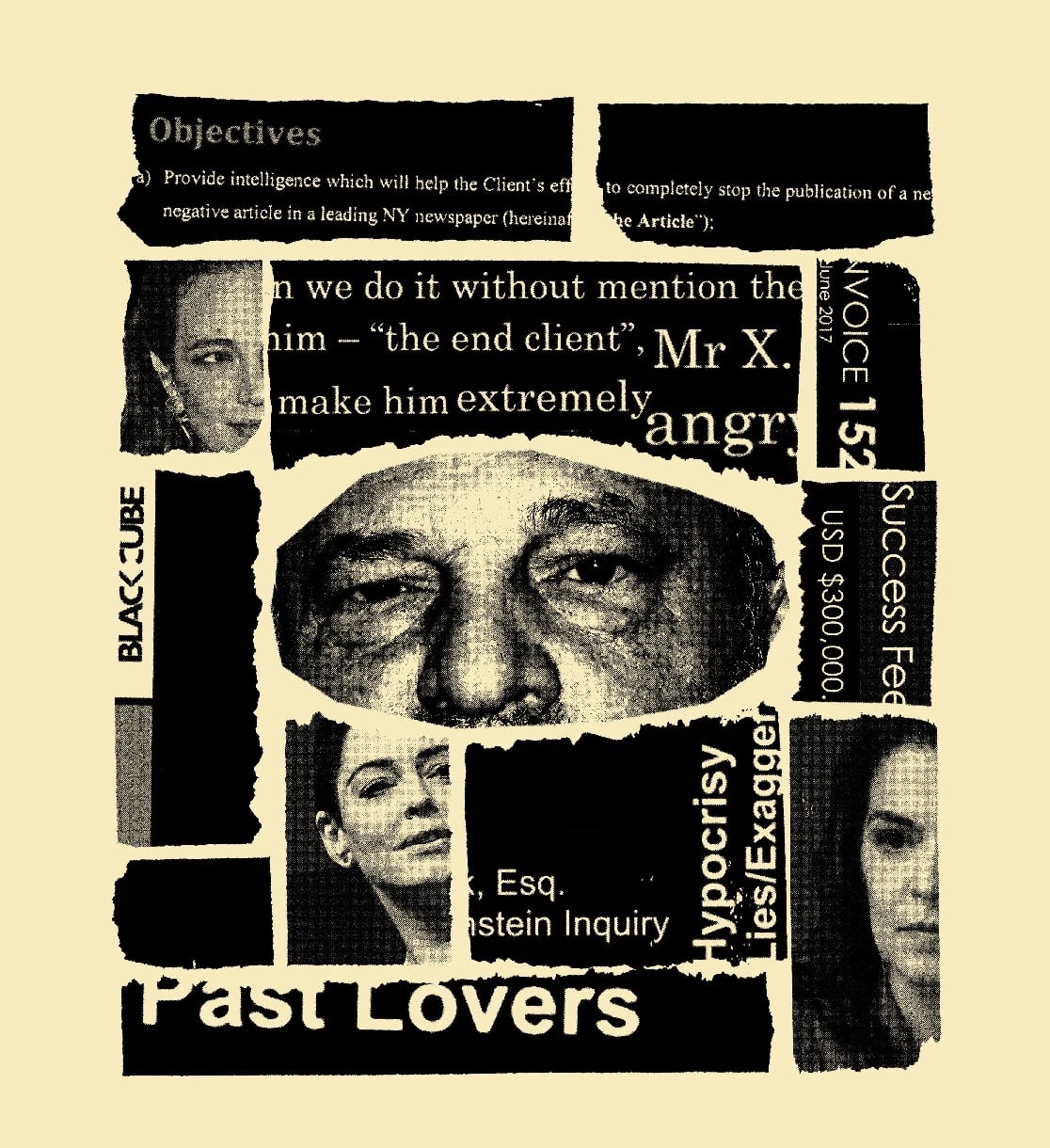

Your last Bit for the weekend takes a look at the tools that powerful men use to hide their crimes and other abuses of power. About a year before the New York Times and The New Yorker published the stories that would end Harvey Weinstein’s career, he hired private investigators to help him find a way to keep the stories from being published; while his efforts were ultimately in vain, Ronan Farrow’s excellent reporting shows the lengths that Weinstein and his conspirators went to silence his victims. Investigators from the firms Kroll and Black Rock, some of whom were originally trained as spies, reached out to Weinstein’s victims and reporters investigating the allegations under false identities. The spies covertly recorded conversations and worked to compile dossiers that could be used to discredit Weinstein’s victims. All of this took place under the oversight of famed liberal defense attorney David Boies, who helped to shroud Weinstein’s tactics so that he might be protected by attorney-client privilege.

Harvey Weinstein’s Army of Spies

~ 26 Minute Read

“All of the security firms that Weinstein hired were also involved in trying to ferret out reporters’ sources and probe their backgrounds. Wallace, the reporter for New York, said that he was suspicious when he received the call from the Black Cube operative using the pseudonym Anna, because Weinstein had already requested a meeting with Wallace; Adam Moss, the editor-in-chief of New York; David Boies; and a representative from Kroll. The intention, Wallace assumed, was to “come in with dossiers slagging various women and me.” Moss declined the meeting.

In a series of e-mails sent in the weeks before Wallace received the call from Anna, Dan Karson, of Kroll, sent Weinstein preliminary background information on Wallace and Moss. “No adverse information about Adam Moss so far (no libel/defamation cases, no court records or judgments/liens/UCC, etc.),” Karson wrote in one e-mail. Two months later, Palladino, the psops investigator, sent Weinstein a detailed profile of Moss. It stated, “Our research did not yield any promising avenues for the personal impeachment of Moss.”

Similar e-mail exchanges occurred regarding Wallace. Kroll sent Weinstein a list of public criticisms of Wallace’s previous reporting and a detailed description of a U.K. libel suit filed in response to a book he wrote, in 2008, about the rare-wine market. psops also profiled Wallace’s ex-wife, noting that she “might prove relevant to considerations of our response strategy when Wallace’s article on our client is finally published.”

In January, 2017, Wallace, Moss, and other editors at New York decided to shelve the story. Wallace had assembled a detailed list of women with allegations, but he lacked on-the-record statements from any victims. Wallace said that the decision not to run a story was made for legitimate journalistic reasons. Nevertheless, he said, “There was much more static and distraction than I’ve encountered on any other story.”

Other reporters were investigated as well. In April, 2017, Ness, of psops, sent Weinstein an assessment of my own interactions with “persons of interest”—a list largely consisting of women with allegations, or those connected to them. Later, psops submitted a detailed report focussing jointly on me and Jodi Kantor, of the Times. Some of the observations in the report are mundane. “Kantor is NOT following Ronan Farrow,” it notes, referring to relationships on Twitter. At other times, the report reflects a detailed effort to uncover sources. One individual I interviewed, and another whom Kantor spoke to in her separate endeavor, were listed as having reported the details of the conversations back to Weinstein.

For years, Weinstein had used private security agencies to investigate reporters. In the early aughts, as the journalist David Carr, who died in 2015, worked on a report on Weinstein for New York, Weinstein assigned Kroll to dig up unflattering information about him, according to a source close to the matter. Carr’s widow, Jill Rooney Carr, told me that her husband believed that he was being surveilled, though he didn’t know by whom. “He thought he was being followed,” she recalled. In one document, Weinstein’s investigators wrote that Carr had learned of McGowan’s allegation in the course of his reporting. Carr “wrote a number of critical/unflattering articles about HW over the years,” the document says, “none of which touched on the topic of women (due to fear of HW’s retaliation, according to HW).”

Weinstein’s relationships with the private investigators were often routed through law firms that represented him. This is designed to place investigative materials under the aegis of attorney-client privilege, which can prevent the disclosure of communications, even in court.

David Boies, who was involved in the relationships with Black Cube and psops, was initially reluctant to speak with The New Yorker, out of concern that he might be “misinterpreted either as trying to deny or minimize mistakes that were made, or as agreeing with criticisms that I don’t agree are valid.”

But Boies did feel the need to respond to what he considered “fair and important” questions about his hiring of investigators. He said that he did not consider the contractual provisions directing Black Cube to stop the publication of the Times story to be a conflict of interest, because his firm was also representing the newspaper in a libel suit. From the beginning, he said, he advised Weinstein “that the story could not be stopped by threats or influence and that the only way the story could be stopped was by convincing the Times that there was no rape.” Boies told me he never pressured any news outlet. “If evidence could be uncovered to convince the Times the charges should not be published, I did not believe, and do not believe, that that would be averse to the Times’ interest.”

He conceded, however, that any efforts to profile and undermine reporters, at the Times and elsewhere, were problematic. “In general, I don’t think it’s appropriate to try to pressure reporters,” he said. “If that did happen here, it would not have been appropriate.””

Click To Read The Full Article At The New Yorker

Thanks for checking out the Weekend Bits! If you enjoyed these Bits, why don’t you share it with a friend? We appreciate your support and as always, Contact Us online or send us an email at [email protected].

Have a great rest of your week!