October 1, 2017

For your Bits this weekend we start by taking a look at pay and career possibilities of a janitor working at Apple’s headquarters in Cupertino, CA in 2017 and comparing it to what was available to someone in the same position at Eastman Kodak in Rochester, NY in the early 1980s; these differences highlight much of the economic trends that have contributed to a new Gilded Age in the United States where profits are disproportionately awarded to capital owners, managers, and those with specialized skills. One major changes in business practices that has facilitated this change is the outsourcing of labor intensive jobs that are not part of a company’s core offerings (e.g. janitorial, security work, product testing) which allows the market to drive down wages and benefits for these roles and prevents these employees from the opportunity of promotions within the firm.

To Understand Rising Inequality, Consider the Janitors at Two Top Companies, Then and Now

~ 18 Minute Read

“Eastman Kodak was one of the technological giants of the 20th century, a dominant seller of film, cameras and other products. It made its founders unfathomably wealthy and created thousands of high-income jobs for executives, engineers and other white-collar professionals. The same is true of Apple today.

But Kodak also created enough working-class jobs to help create two generations of middle-class wealth in Rochester. The Harvard economist Larry Summers has often pointed at this difference, arguing that it helps explain rising inequality and declining social mobility.

“Think about the contrast between George Eastman, who pioneered fundamental innovations in photography, and Steve Jobs,” Mr. Summers wrote in 2014. “While Eastman’s innovations and their dissemination through the Eastman Kodak Co. provided a foundation for a prosperous middle class in Rochester for generations, no comparable impact has been created by Jobs’s innovations” at Apple.

Ms. Evans’s pathway was unusual: Few low-level workers, even in the heyday of postwar American industry, ever made it to the executive ranks of big companies. But when Kodak and similar companies were in their prime, tens of thousands of machine operators, warehouse workers, clerical assistants and the like could count on steady work and good benefits that are much rarer today.

When Apple was seeking permission to build its new headquarters, its consultants projected the company would have 23,400 employees, with an average salary comfortably in the six figures. Thirty years ago, Kodak employed about 60,000 people in Rochester, with average pay and benefits companywide worth $79,000 in today’s dollars.

Part of the wild success of the Silicon Valley giants of today — and what makes their stocks so appealing to investors — has come from their ability to attain huge revenue and profits with relatively few workers.

Apple, Alphabet (parent of Google) and Facebook generated $333 billion of revenue combined last year with 205,000 employees worldwide. In 1993, three of the most successful, technologically oriented companies based in the Northeast — Kodak, IBM and AT&T — needed more than three times as many employees, 675,000, to generate 27 percent less in inflation-adjusted revenue.

The 10 most valuable tech companies have 1.5 million employees, according to calculations by Michael Mandel of the Progressive Policy Institute, compared with 2.2 million employed by the 10 biggest industrial companies in 1979. Mr. Mandel, however, notes that today’s tech industry is adding jobs much faster than the industrial companies, which took many decades to reach that scale.

Many of the professional jobs from those companies in the 1980s and ’90s have close parallels today. The high-paying positions setting corporate strategy, developing experimental technologies and shaping marketing campaigns would look similar in either era.

But a generation ago, big companies also more often directly employed people who installed products, moved goods around warehouses, worked as security guards and performed many of the other jobs needed to get products into the hands of consumers.

In part, fewer of these kinds of workers are needed in an era when software plays such a big role. The lines of code that make an iPhone’s camera work can be created once, then instantly transmitted across the globe, whereas each roll of film had to be manufactured and physically shipped. And companies face brutal global competition; if they don’t keep their work force lean, they risk losing to a competitor that does.

But major companies have also chosen to bifurcate their work force, contracting out much of the labor that goes into their products to other companies, which compete by lowering costs. It’s not just janitors and security guards. In Silicon Valley, the people who test operating systems for bugs, review social media posts that may violate guidelines, and screen thousands of job applications are unlikely to receive a paycheck directly from the company they are ultimately working for.

And the phenomenon stretches far beyond Silicon Valley, where companies like Apple are just a particularly extreme example of achieving huge business success with a relatively small employee count. The Federal Express delivery person who brings you a package may well be an independent contractor; many of the people who help banks like Citigroup and JPMorgan service mortgage loans and collect delinquent payments work for contractors; and if you call your employer’s computer help desk, there’s a good chance it will be picked up by someone in another state, or country.”

Click To Read The Full Article At The New York Times

Our next article takes a look at the Air Force Missileers who are charged with the mission of maintaining the systems that allow for the United States to launch nuclear-capable intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) at a moment’s notice. In teams of two, missileers work in capsules that are 60-80 feet below ground and protected by 8-ton blast doors for 24-hour shifts, waiting on an order that could end the world. The protocol for missileers is simple: Copy. Decode. Validate. Authenticate. “‘It is a very precise method,’ Barrington explains. ‘It’s not haphazard. It is exacting. Missileers have to know all kinds of rules. They have to know it cold.’” The rest of us can only hope that the order never comes.

These Women Are the Last Thing Standing Between You and Nuclear War

~ 16 Minute Read

“Older missileers thought for sure during the Cold War that they would get the order to launch, but it never came,” says Dinkha. And she’s right: America hasn’t used a nuke since 1945. So what exactly goes on down in those capsules?

“Our mission every day is to provide deterrence,” offers Moore. “Every day we try to make our enemies ask themselves the question, Does the benefit of attacking the U.S. outweigh the cost? Because they know that we’re always prepared to fire back.” Readiness is imperative. A missileer’s day-to-day is a lot of maintenance, a lot of making sure each ICBM is in tip-top shape, able to sail over the arctic circle instantaneously.

Barrington likens our missiles to a car in idle mode. But the analogy actually goes a bit further: It’s like the U.S. government left a car in a lot (okay, an underground lot) with the keys in the ignition and the engine running…and these officers are trying to keep tabs on it remotely…and, actually, they’re dealing with quite a few cars.

Each missile is three nautical miles from a capsule, and each team of two missileers is responsible for 10. The missiles are also buried below ground, surrounded by fields of sunflowers and flax—by cattle farms, oil rigs, and wind turbines. Fifteen-hundred miles of cabling connects the missileers to their missiles, though they can also communicate with the machines via satellite or low-frequency waves—myriad redundancies are in place in case of emergency or catastrophe or, hell, just a North Dakotan winter storm. Constantly these troopers ping their weapons, gathering status updates: Are they overheating? Too cold? Low on fuel? Did the power go out? Is there a security breach near the missile silo? When an issue arises, they fix it immediately or dispatch another airman to do so.

“There are definitely those shifts that make up for all the quiet ones you’ve ever had,” laments Dinkha. “Where you just stay up for 30 hours because everything that could go wrong does go wrong.” (Both women say the longest they’ve pulled crew is 48 hours, though they know missileers who have worked a 72. Sometimes the snow is just too heavy and the roads too treacherous to get another crew out to the capsule.)

They’re doing all of this, by the way, on a computer that looks like it should be part of a history exhibit at the National Air and Space Museum. Aside from a few “programs to refurbish and rebuild,” the equipment is the same as it was in the 1970s—the missileers code their commands using 0s and 1s. At first it seems like another example of the government being behind the times, but then you remember Sony and the DNC and you realize, Maybe updating the systems would actually be more dangerous than doing things the old-fashioned way. “You can’t just stick laptops down there and say, ‘Now you are going to get messages via email,'” Barrington says.

Being cut off from modern tech can make slow days in the capsule feel even slower. “At first you’re both awake and you’re going over your inspections, and it gives you time to get to know that person, because you may not really ever talk to that person and then you are expected to go hang out in close quarters for 24 hours,” says Moore, adding that later they break the day into shifts. Whoever’s on the night shift naps early, then takes the console around 10 p.m. while the other sleeps until about 5:30 in the morning. That’s a lot of time to fill and—thanks to the moratorium on wifi-capable electronics—you can’t exactly spend it scrolling Instagram.

“I got my master’s in education done while I was down there,” Moore says. “Once I retire from the Air Force, I plan to teach 5th or 6th grade science.” She used to bring art supplies down and paint (watercolors only—you don’t want to be that person using oils in a confined space). Ditto for riding the exercise bike that’s stashed in a corner, especially since there isn’t a shower. “I do a lot of push-ups and sit-ups,” she adds, noting that “they’re not gonna get you extremely sweaty if you do them in small doses.””

Click To Read The Full Article At Marie Claire

Your last Bit for the weekend takes a look at LSD and how it has been used and perceived within Silicon Valley over the past 50 years. LSD’s effects are caused by its interactions with serotonin in the user’s brain and research has shown that its impact is most heavily expressed in the cortex, the part of the brain from which consciousness is believed to arise. Since the 1960s, the emerging tech community has viewed LSD more favorably than the rest of the United States and it has been valued for its perceived ability to increase creativity in users. Over the past few years, some in the tech community are going even further and adopting a practice known as micro-dosing; taking 1/10th of a normal LSD dose every few days and going about a normal workday. Though formal research on the practice is non-existent, practitioners have reported increases in focus, self awareness, purpose, and confidence without addictive or other negative side effects.

Turn On, Tune In, Drop By The Office

~ 14 Minute Read

“From the start, a small but significant crossover existed between those who were experimenting with drugs and the burgeoning tech community in San Francisco. “There were a group of engineers who believed there was a causal connection between creativity and LSD,” recalls John Markoff, whose 2005 book, “What the Dormouse Said”, traces the development of the personal-computer industry through 1960s counterculture. At one research centre in Menlo Park over 350 people – particularly scientists, engineers and architects – took part in experiments with psychedelics to see how the drugs affected their work. Tim Scully, a mathematician who, with the chemist Nick Sand, produced 3.6m tabs of LSD in the 1960s, worked at a computer company after being released from his ten-year prison sentence for supplying drugs. “Working in tech, it was more of a plus than a minus that I worked with LSD,” he says. No one would turn up to work stoned or high but “people in technology, a lot of them, understood that psychedelics are an extremely good way of teaching you how to think outside the box.”

San Francisco appears to be at the epicentre of the new trend, just as it was during the original craze five decades ago. Tim Ferriss, an angel investor and author, claimed in 2015 in an interview with CNN that “the billionaires I know, almost without exception, use hallucinogens on a regular basis.” Few billionaires are as open about their usage as Ferriss suggests. Steve Jobs was an exception: he spoke frequently about how “taking LSD was a profound experience, one of the most important things in my life”. In Walter Isaacson’s 2011 biography, the Apple CEO is quoted as joking that Microsoft would be a more original company if Bill Gates, its founder, had experienced psychedelics.

As Silicon Valley is a place full of people whose most fervent desire is to be Steve Jobs, individuals are gradually opening up about their usage – or talking about trying LSD for the first time. According to Chris Kantrowitz, the CEO of Gobbler, a cloud-storage company, and the head of a new fund investing in psychedelic research, people were refusing to talk about psychedelics as recently as three years ago. “It was very hush hush, even if they did it.” Now, in some circles, it seems hard to find someone who has never tried it.

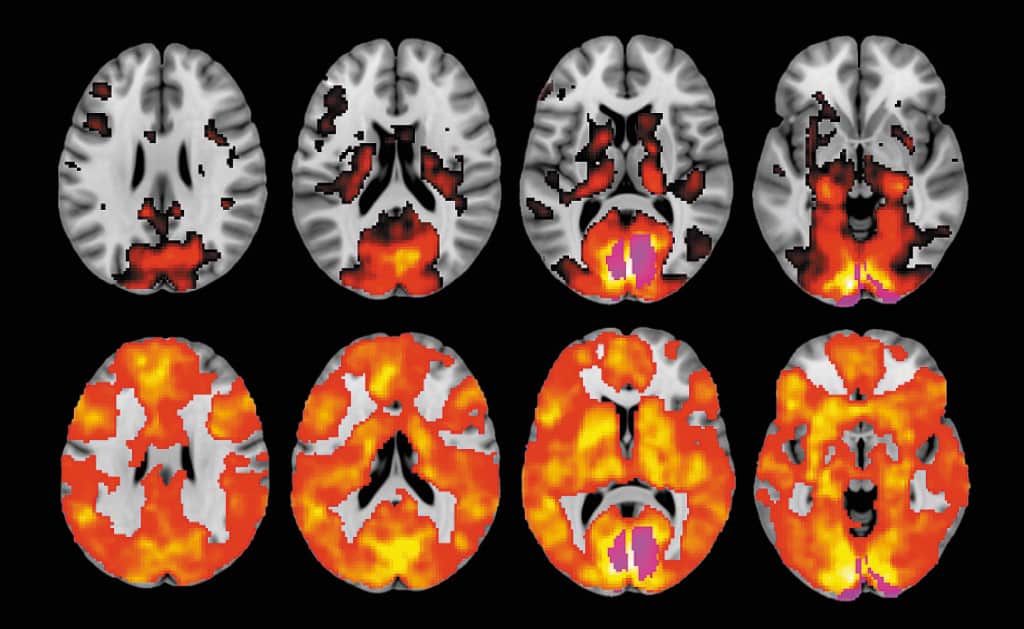

LSD works by interacting with serotonin, the chemical in the brain that modulates mood, dreaming and consciousness. Once the drug enters the brain (no mean feat), it hijacks the serotonin 2A receptor, explains Robin Carhart-Harris, a scientist at Imperial College London who is among those mapping out the effects of psychedelics using brain-scanning technology. The 2A receptor is most heavily expressed in the cortex, the part of the brain in which consciousness could be said to reside. One of the first effects of psychedelics such as LSD is to “dissolve a sense of self,” says Carhart-Harris. This is why those who have taken the drug sometimes describe the experience as mystical or spiritual.

The drug also seems to connect previously isolated parts of the brain. Scans from Carhart-Harris’s research, conducted with the Beckley Foundation in Oxford, show a riot of colour in the volunteers’ brains, compared with those who have taken a placebo. The volunteers who had taken LSD did not just process those images they had actually seen in their visual cortexes; instead many other parts of the brain started processing visions, as though the subject was seeing things with their eyes shut. “The brain becomes more globally interconnected,” says Carhart-Harris. The drug, by acting on the serotonin receptor, seems to increase the excitability of the cortex; the result is that the brain becomes far “more open”.

In an intensely competitive culture such as Silicon Valley, where everyone is striving to be as creative as possible, the ability for LSD to open up minds is particularly attractive. People are looking to “body hack”, says Kantrowitz: “How do we become better humans, how do we change the world?” One CEO of a small startup describes how, on an away-day with his company, everyone took magic mushrooms. It allowed them to “drop the barriers that would typically exist in an office”, have “heart to hearts”, and helped build the “culture” of the company. (He denied himself the pleasure of partaking so that he could make sure everyone else had a good time.) Eric Weinstein, the managing director of Thiel Capital, told Rolling Stone magazine last year that he wants to try and get as many people to talk openly about how they “directed their own intellectual evolution with the use of psychedelics as self-hacking tools”.”

Click To Read The Full Article At 1843Magazine.com

Thanks for checking out the Weekend Bits! If you enjoyed these Bits, why don’t you share it with a friend? We appreciate your support and as always, Contact Us online or send us an email at [email protected].

Have a great rest of your week!