September 24, 2017

For your Bits this weekend we start off by taking a look into the world of polyamory, a term that can refer to a number of different types of romantic and sexual relationships that involve more than two people. Not to be confused with “prairie-dress-clad fundamentalist polygamists,” polys, as they are sometimes called, come in my forms including: bisexuals/pansexuals who may want relationships with partners of various gender identities, kinksters looking for sexual variety, or couples who don’t view sexual exclusivity as a key part of their relationships. Sometimes polys will live and date in groups or sometimes they will have primary partners and date others independently. Whichever form these relationships takes, monogamists can often benefit from learning how polys manage jealousy and use active communication to create a happy and loving environment for their intimate relationships.

Multiple Lovers, Without Jealousy

~ 27 Minute Read

“Those of us who are in monogamous relationships will probably never stop being jealous—and that’s healthy. What’s not healthy is the way some monogamous people manipulate their partners’ jealousy and devotion. According to Shackelford, women in monogamous relationships “are more likely to use sexual assets to induce jealousy in their partner,” while “men will manipulate access to resources.”

By contrast, the way polyamorous people tend to resolve their conflicts is more above-board. When extramarital relations are already out in the open, it seems there’s little else to hide. “A big part of what makes someone feel jealous is when their expectations for the relationship are violated,” Theiss said. “In poly situations, where they’ve actually negotiated the ground rules—‘I care about you and I also care about this other person, and that doesn’t mean I care less about you’—that creates a foundation that means [they] don’t have to feel jealous. They don’t have uncertainty about what’s happening.”

For example, as Conley, the polyamory researcher, has noted, “polyamory writings explicitly advocate that people revisit and reevaluate the terms of their relationships regularly and consistently—this practice could benefit monogamous relationships as well. Perhaps a monogamous couple deemed dancing with others appropriate a year ago, but after revisiting this boundary they agree that it is stressful and should be eliminated for the interim.”

People in plural relationships get jealous, too, of course. But the way polys get jealous is unique—and possibly even adaptive. Rather than blame the partner for their feelings, the polys view the jealousy an irrational symptom of their own self-doubt.

Cassie and Josh had been dating a woman—let’s call her Anne—for about a year and a half when all three went to a diner together. Josh, who doesn’t like tomatoes, ordered a burger. Cassie went to the bathroom. When she came back, the burger had arrived and Anne was eating Josh’s tomatoes.

Cassie loves tomatoes—and she always eats Josh’s tomatoes.

“They were my freaking tomatoes,” she said. “I had experienced the loss of my tomatoes, and that was a unique thing for me.”

“I was going to be angry and scream, but then I thought, ‘This is just tomatoes.’”

Rather than throw a tantrum or banish Anne from the triad, Cassie simply waited to cool off about the tomatoes, and the three moved on.

“I think everyone feels jealous,” Josh said. “Us and the people we’ve dated and most of the people I know feel jealous. But when I think of jealousy, I think of it more as it’s another emotion we express as jealousy. You’re not actually jealous; you’re feeling loss.”

“I had revelations about jealousy back when I was trying to be monogamous,” said Jonica, the 27-year-old living in the triad in Virginia. She realized “it’s kinda silly. It produces the opposite effect that you supposedly want. If I was jealous of my lover, and I start acting out on that emotion, it’s going to drive that person away from me.”

Stew, the man in the open relationship, says that whenever jealousy surfaces, he and his partners recognize it as “one or more specific unmet needs, like wanting more date-like time together.”

For example, his main partner, M, was recently feeling jealous that he was spending so much time with B, his girlfriend, and feared that Stew would eventually want to leave M for B. M “knows in her logical brain that this isn’t the case, but thoughts like these are worries, like ‘Did I leave the stove on?’” Stew said. “You can’t logic them away.”

So on top of reassuring M that he would never leave her, in times like these, Stew tries to lighten the mood “with a nice walk around the block, or making dinner with her, or being silly, or watching Netflix.”

“We’re in a place where, for the most part, we both are able to see feelings of envy and insecurity for what they are, and we have a deep bond of trust that is most often very easily accessible, which we can reach out to and touch when we need to remind ourselves that it’s there,” he said.

Josh and Cassie talk over and negotiate everything—“a lot more than other couples do,” they think. The tomatoes were such a big deal because their allotment hadn’t been previously agreed upon. (In the end, the three decided they would share all future tomatoes.)

Overall, Josh says sharing a life between three adults, rather than two, is not as kinky and complicated as some monogamous people might think. “The stuff in poly that’s difficult is not the sex,” he said. “It’s where the goddamn spoons get put away.”

In that sense, at least, poly and mono relationships are more alike than they are different.”

Click To Read The Full Article At The Atlantic

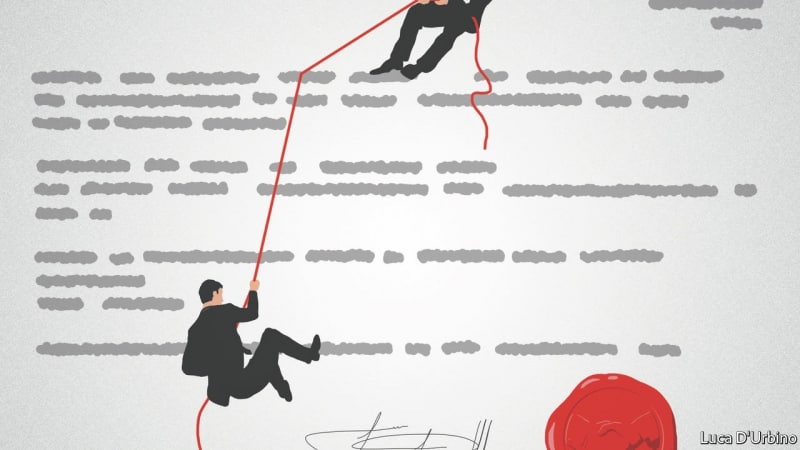

Our next article takes a look at one of the central oversights of “classical” economics: why some economic activities are directed by firms rather than solely by market forces. An answer was first proposed in the 1930s by Ronald Coase who noticed that firms were simply a market solution for creating a more efficient way to complete tasks; given that there exist high costs for using markets, it’s easier to get a market participant (i.e. an employee) to agree to perform certain tasks (i.e. a job) for a predetermined sum (i.e. a salary) than to have them barter their services on the open market. This allows the firm to engage with other market participants (e.g. other firms or consumers) to provide products and services of value by directing the output of their employees. This theory had ramifications across the field of economics and has led to further research on property rights, social contracts, transaction costs providing better explanatory mechanisms for business practices from franchising to employment contracts for salespeople.

Coase’s Theory Of The Firm

~ 15 Minute Read

“If a team of workers requires a firm as monitor, might that also be true for teams of suppliers? In some cases, firms are indeed vertically integrated, meaning that suppliers of inputs and producers of final goods are under the same ownership. But in other cases, suppliers and their customers are separate entities. When is one set-up right and not the other?

A paper published in 1986 by Sanford Grossman and Mr Hart sharpened the thinking on this. They distinguished between two types of rights over a firm’s assets (its plant, machinery, brands, client lists and so on): specific rights, which can be contracted out, and residual rights, which come with ownership. Where it becomes costly for a company to specify all that it wants from a supplier, it might make sense to acquire it in order to claim the residual rights (and the profits) from ownership. But, as Messrs Grossman and Hart noted, something is also lost through the merger. The supplier’s incentive to innovate and to control costs vanishes, because he no longer owns the residual rights.

To illustrate this kind of relationship, they used the example of an insurance firm that pays a commission to an agent for selling policies. To encourage the agent to find high-quality clients, which are more likely to renew a policy, the firm defers some portion of the agent’s pay and ties it to the rate of policy renewals. The agent is thus induced to work hard to find good clients. But there is a drawback. The insurance firm now has an incentive of its own to shirk. While the agent is busting a gut to find the right sort of customers, the firm can take advantage by, say, cutting its spending on advertising its policies, raising their price or lowering their quality.

There is no set-up in which the incentives of firm and agent can be perfectly aligned. But Messrs Grossman and Hart identified a next-best solution: the party that brings the most to any venture in terms of “non-contractible” effort should own the key assets, which in this case is the client list. So the agent ought to own the list wherever policy renewals are sensitive to sales effort, as in the case of car insurance, for which people tend to shop around more. The agent would keep the residual rights and be rewarded for the effort to find the right sort of client. If the insurance firm shirks, the agent can simply sell the policies of a rival firm to his clients. But in cases where the firm brings more to the party than the sales agent—for example, when clients are “stickier” and the first sale is crucial, as with life insurance—a merger would make more sense.

This framework helps to address one of the questions raised by Coase’s original paper: when should a firm “make” and when should it “buy”? It can be applied to vertical business ties of all kinds. For instance, franchises have to abide by a few rules that can be set down in a contract, but get to keep the residual profits in exchange for a royalty fee paid to the parent firm. That is because the important efforts that the parent requires of a franchisee are not easy to put in a contract or to enforce.”

Click To Read The Full Article At The Economist

Your last Bit this weekend revisits the intelligence dossier compiled by Christopher Steele of Orbis Business Intelligence. This dossier makes a number of allegations concerning U.S. President Donald Trump, most infamously about specific sexual fetishes in Moscow hotel rooms, that suggest that the Kremlin could have some sort of Kompromat (i.e. blackmail) regarding Trump. Written by a coalition of security experts, the article evaluates a number of claims from the dossier and finds that it matches up surprisingly well with facts that have since been discovered from media reports of Congressional, FBI, and Special Counsel investigations. For example, the versions of the report from as early as June 2016 indicated that Russia would undertake a coordinated cyber attack leaking documents about Clinton associates, which was many months before any of these events occurred or this information was confirmed by U.S. intelligence services. Particular attention is also paid to the process by which the FBI engaged with the dossier, going so far as to pay Orbis to continue its work, as “there is nobody more miserly than the FBI. If they were willing to pay Mr. Steele, they must have seen something of real value.”

The Steele Report, Revisited

~ 24 Minute Read

“So how should we unpack the Steele dossier from an intelligence perspective?

I spent almost 30 years producing what CIA calls “raw reporting” from human agents. At heart, this is what Orbis did. They were not producing finished analysis, but were passing on to a client distilled reporting that they had obtained in response to specific questions. When disseminating a raw intelligence report, an intelligence agency is not vouching for the accuracy of the information provided by the report’s sources and/or subsources. Rather it is claiming that it has made strenuous efforts to validate that it is reporting accurately what the sources/subsources claim has happened. The onus for sorting out the veracity and for putting the reporting in context against other reporting—which may confirm or disconfirm the reporting—rests with the intelligence community’s professional analytic cadre. In the case of the dossier, Orbis was not saying that everything that it reported was accurate, but that it had made a good-faith effort to pass along faithfully what its identified insiders said was accurate. This is routine in the intelligence business. And this form of reporting is often a critical product in putting together more final intelligence assessments.

Steele’s product is not a report delivered with a bow at the end of an investigation. Instead, it is a series of contemporaneous raw reports that do not have the benefit of hindsight. Among the unnamed sources are “a senior Russian foreign ministry official,” “a former top-level intelligence officer still active inside the Kremlin,” and “a close associate of Republican U.S. presidential candidate Donald Trump.” Thus, the reports are not an attempt to connect the dots, but instead an effort to uncover new and potentially relevant dots in the first place.

Let me illustrate what the reports contain by unpacking the first and most notorious of the 17 Orbis reports, and then move to some of the other ones. The first two-and-a-half page report was dated June 20, 2016, and entitled “Company Intelligence Report 2016/080.” It starts with several summary bullets and continues with additional detail attributed to sources A through E and G (there may be a source F but part of the report is blacked out). The report makes a number of explosive claims, all of which at the time of the report were unknown to the public.

Among other assertions, three sources in the Orbis report describe a multi-year effort by Russian authorities to cultivate, support, and assist Donald Trump. According to the account, the Kremlin provided Trump with intelligence on his political primary opponents and access to potential business deals in Russia. Perhaps more importantly, Russia had offered to provide potentially compromising material on Hillary Clinton, consisting of bugged conversations during her travels to Russia, and evidence of her viewpoints that contradicted her public positions on various issues.

The report also alleged that the internal Russian intelligence service, FSB, had developed potentially compromising material on Trump, to include details of “perverted sexual acts” which were arranged and monitored by the FSB.

The report stated that Russian President Putin was supportive of the effort to cultivate Trump, and the primary aim was to sow discord and disunity within the U.S. and the West. The dossier of FSB-collected information on Hillary Clinton was purportedly managed by Kremlin chief spokesman Dimitry Peskov.

Subsequent reports provide additional detail about the possible conspiracy, which includes information about cyberattacks against the U.S. They allege that former Trump campaign chief Paul Manafort managed the plot to exploit political information on Hillary Clinton in return for information on Russian oligarchs outside Russia, and an agreement to “sideline” Ukraine as a campaign issue. According to the report, Trump campaign operative Carter Page is also said to have played a role in shuttling information to Moscow, while Trump’s personal lawyer, Michael Cohen, reportedly took over efforts after Manafort left the campaign, allegedly providing cash payments for Russian hackers. In one account, Putin and his aides expressed concern over kickbacks of cash to Manafort from former Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych, which they feared might be discoverable by U.S. authorities. The Kremlin also feared that the U.S. might stumble onto the conspiracy through the actions of a Russian diplomat in Washington, Mikhail Kalugin, and therefore had him withdrawn, according to the reports.

In late fall 2016, the Orbis team reported that a Russian-supported company had been “using botnets and porn traffic to transmit viruses, plant bugs, steal data and conduct ‘altering operations’ against the Democratic Party leadership.” Hackers recruited by the FSB under duress were involved in the operations. According to the report, Cohen insisted that payments be made quickly and discreetly, and that cyber operators should go to ground and cover their tracks.

What should be made of these leaked reports with unnamed sources on issues that were deliberately concealed by the participants? Honest media outlets have reported on subsequent events that appear to be connected to the reports, but do not go too far with their analysis, concluding still that the dossier is unverified. Almost no outlets have reported on the salacious sexual allegations, leaving the public with very little sense as to whether the dossier is true, false, important, or unimportant in that respect.

While the reluctance of the media to speculate as to the value of the report is understandable, professional intelligence analysts and investigators do not have the luxury of simply dismissing the information. They instead need to do all they can to put it into context, determine what appears credible, and openly acknowledge the gaps in understanding so that collectors can seek additional information that might help make sense of the charges.

In the intelligence world, we always begin with source validation, focusing on what intelligence professionals call “the chain of acquisition.” In this case we would look for detailed information on (in this order) Orbis, Steele, his means of collection (e.g., who was working for him in collecting information), his sources, their sub-sources (witting or unwitting), and the actual people, organizations and issues being reported on.

Intelligence methodology presumes that perfect information is never available, and that the vetting process involves cross-checking both the source of the information as well as the information itself. There is a saying among spy handlers, “vet the source first before attempting to vet the source’s information.” Information from human sources (the spies themselves) is dependent on their distinct access to information, and every source has a particular lens. Professional collectors and debriefing experts do not elicit information from a source outside of the source’s area of specific access. They also understand that inaccuracies are inevitable, even if the source is not trying to mislead. The intelligence process is built upon a feedback cycle that corroborates what it can, and then goes back to gather additional information to help build confidence in the assessment. The process is dispassionate, unemotional, professional, and never-ending.”

Click To Read The Full Article At Slate.com

Thanks for checking out the Weekend Bits! If you enjoyed these Bits, why don’t you share it with a friend? We appreciate your support and as always, Contact Us online or send us an email at [email protected].

Have a great rest of your week!